Wurtsmith Air Force Base (Wurtsmith) has nearly 60 volatile chemical contamination sites. The volatile chemicals were jet fuel, engine degreaser, gasoline, kerosene, and the like. For clarity, toxic firefighter foam is not a volatile chemical and its contamination of Wurtsmith’s people and environment is its own story; read our previous blog posts to learn more about the PFAS groundwater contamination from firefighter foam and how military families living and working on Wurtsmith drank large quantities of this toxic chemical from 1985 to 1992. Two volatile chemical contamination sites caused the most harm, resulting in large groundwater plumes in the space between the top soil and roughly 65 feet below the surface where clay creates a nearly impermeable barrier. Both groundwater plumes reached the faucets on base. It was not until 1977 that any chemical contamination of the groundwater became an unavoidable issue at Wurtsmith. I was stationed at Wurtsmith from 1986 to 1990. The impact of my wife drinking contaminated water during her pregnancy was catastrophic. We wrote a book sharing our 30-year story so others could understand how the poisons of war can irrevocable change the life of just one military family. We know that there are many untold stories; stories we plan to share in future ‘Wurtsmith Water’ blog posts. Our story will change you, and is available on Amazon.

VETERAN ALERT! Veterans, civilians, and their families (spouses, pregnant mothers, and children) living and working on the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base drank TCE and other volatile chemicals from 1962 through April 1980. The volatile chemical groundwater consumption at former Wurtsmith is similar in scope to the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune veteran and family drinking water contamination in North Carolina. According to the VA, “Veterans who served at Camp Lejeune or MCAS New River for at least 30 cumulative days from August 1953 through December 1987—and their family members—can get health care benefits.” The same should be true for veterans and their family members at former Wurtsmith Air Force Base.

| ACTION REQUIRED: The first step is to learn as much as you can about the chemical contaminations at Wurtsmith Air Force Base. The second step is to respectfully engage and educate local, state, and federal government officials on what really happened before all those impacted disappear to eternity. Let’s not leave this story exclusively to the historians. |

Engine Degreaser in The Base Water Supply 1962-1980: Arrow Street Plume

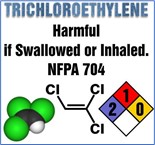

Veterans and their families living and working on the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base drank engine degreaser and other volatile chemicals in the base drinking water supply system (distributed through the water tower) from as early as 1962 through 1980. The engine degreaser was Trichlorethylene (TCE) and is a volatile chemical. The known health impacts from drinking TCE are well documented by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). The ATSDR is the federal public health agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The first Wurtsmith health assessment was published by the ATSDR in 2001. A second health assessment was published in 2018. It is now 43 years since TCE contamination was first discovered in the faucets of base housing residents.

| WARNING! Veterans and their families living and working on the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base drank used engine degreaser (trichloroethylene or TCE) and other volatile chemicals in the base drinking water (distributed through the water tower) from 1962 through 1980. TCE was discovered in base resident faucets in 1977. The leaking tank was installed in 1962 and removed in 1977. Incremental remediation reduced TCE to what was considered acceptable levels in 1980. This is the Arrow Street Plume and groundwater purging continues to this day. |

Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina experienced a similar volatile chemical ground water contamination from 1953 through 1987. According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (Veterans Administration or VA), “Scientific and medical evidence has shown an association between exposure to these contaminants during military service and development of certain diseases later on…the VA recognizes the diagnosis of one or more of these presumptive conditions:

- Adult leukemia

- Aplastic anemia and other myelodysplastic syndromes

- Bladder cancer

- Kidney cancer

- Liver cancer

- Multiple myeloma

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Parkinson’s disease”

According to the VA, “Veterans who served at Camp Lejeune or MCAS New River for at least 30 cumulative days from August 1953 through December 1987—and their family members—can get health care benefits. We may pay you back for your out-of-pocket health care costs that were related to any of these 15 conditions:

- Bladder cancer

- Breast cancer

- Esophageal cancer

- Female infertility

- Hepatic steatosis

- Kidney cancer

- Leukemia

- Lung cancer

- Miscarriage

- Multiple myeloma

- Myelodysplastic syndromes

- Neurobehavioral effects

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Renal toxicity

- Scleroderma”

Clearly, the precedence has been set to provide health care benefits for veterans and their families poisoned by drinking contaminated groundwater on a military installation. Former Wurtsmith veterans, civilians, and their families need to encourage local, state, and federal government officials to provide the same level of health care benefits for those harmed by TCE and other volatile chemicals in the drinking water from 1962 through 1980.

Following is the TCE groundwater contamination story as this toxic and volatile chemical was drawn into the main drinking wells at Wurtsmith. The story begins in 1977 when base officials received complaints that the tap water smelled and tasted bad. The base civil engineering group responded by testing the water. Test results confirmed chemicals were pouring out of the base housing faucets. The offending wells were taken off line. By October 1977 Investigators discovered the source was a leaking 500-gallon underground storage tank full of a chemical used to degrease engine parts next to Building 43. The tank was in  the ground from 1962 to 1977. When investigators dug up the tank, they discovered a leak near the filler pipe. When the tank began to leak is unknown. Once the tank was full, reports state that the contents of the tank were disposed of in an approved manner. However, there are no surviving records of when the tank was emptied after it was thought to be full. Investigators would estimate that 5000-gallons of used engine degreaser went into the tank while in service. Because the leak was somewhere before the filler pipe (meaning the leak was somewhere near the top of the tank before the filler pipe), it is not hard to imagine airman pouring used degreaser chemicals that would leak directly into the soil after filling the tank up to the level of the leak. Unless the filler pipe was overflowing, there would be no indication that the tank was full. According to the USGS report, there were too many unknowns for investigators to estimate the amount of used degreaser entering the groundwater. In the beginning, the Building 43 underground storage tank leak was known as the “Building 43 Plume.” Building 43 was the Jet Engine Repair Shop at Wurtsmith AFB. After the base closed in 1993, this contamination plume was renamed the “Arrow Street Plume.” Eventually the site simply became SS-21. The chemical content of the building 43 tank was trichloroethylene (TCE) loaded with the remnants of other contaminants from degreasing aircraft and equipment parts. Once the contents of the tank hit the subsoil’s groundwater, the chemicals stratified where the denser chemicals (denser than water) descended deeper into the aquifer than the less dense chemicals. Over time, decomposition of the chemicals produced new chemicals.

the ground from 1962 to 1977. When investigators dug up the tank, they discovered a leak near the filler pipe. When the tank began to leak is unknown. Once the tank was full, reports state that the contents of the tank were disposed of in an approved manner. However, there are no surviving records of when the tank was emptied after it was thought to be full. Investigators would estimate that 5000-gallons of used engine degreaser went into the tank while in service. Because the leak was somewhere before the filler pipe (meaning the leak was somewhere near the top of the tank before the filler pipe), it is not hard to imagine airman pouring used degreaser chemicals that would leak directly into the soil after filling the tank up to the level of the leak. Unless the filler pipe was overflowing, there would be no indication that the tank was full. According to the USGS report, there were too many unknowns for investigators to estimate the amount of used degreaser entering the groundwater. In the beginning, the Building 43 underground storage tank leak was known as the “Building 43 Plume.” Building 43 was the Jet Engine Repair Shop at Wurtsmith AFB. After the base closed in 1993, this contamination plume was renamed the “Arrow Street Plume.” Eventually the site simply became SS-21. The chemical content of the building 43 tank was trichloroethylene (TCE) loaded with the remnants of other contaminants from degreasing aircraft and equipment parts. Once the contents of the tank hit the subsoil’s groundwater, the chemicals stratified where the denser chemicals (denser than water) descended deeper into the aquifer than the less dense chemicals. Over time, decomposition of the chemicals produced new chemicals.

The base immediately stopped using the water from the wells spoiled by the Building 43 Plume. Five months later, Civil Engineering would use a couple of the decommissioned wells to try to purge the TCE from the aquifer. These wells were not located near the tank. For this reason, the purging process did not significantly begin until roughly seven months after digging three new purging wells near the location of the leak. By August 1979, the base would add three more purging wells around the same location, bringing the total to six. The contaminated purge water went to the base’s wastewater treatment plant and after treatment to a seepage lagoon. Sometime after the first purging began in March 1977, the construction of two aeration reservoirs would begin to remove some of the TCE present before sending the water to the waste treatment plant. In the fall of 1979, Civil Engineering added carbon filtration after the aeration reservoirs to remove the remaining TCE before sending the water to the waste treatment plant. Unfortunately, the first two-and-a-half years of pulling TCE and other contaminants out of the groundwater resulted in transferring an untold amount of TCE back into the groundwater at the seepage lagoon. By November 1981, the USGS estimates the removal of 580 gallons of TCE from the groundwater near Building 43. By June 1985, a year before I was stationed at Wurtsmith, the USGS claims to have removed another 320 gallons. Purging of the TCE form the Arrow Street Plume and other volatile chemical compounds continues to this day.

Jet Fuel in The Base Water Supply 1970s-1985: Benzene Plume

Because of the Building 43 underground storage tank leak, broader testing of all the base water sources led to the discovery of more groundwater contamination plumes. While the USGS was finishing its second and final water resource investigation report in 1985, Wurtsmith AFB officials took the lead on the contamination issue by initiating an official Installation Restoration Program (IRP). The official beginning of the IRP was October 1984. The Installation Restoration Program is an Air Force wide program to identify, characterize, and remediate past environmental contamination on installations.

| CAUTION! Veterans and their families living and working on the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base drank an undetermined amount of jet fuel and various other volatile chemicals like Benzene and Toluene drawn in to the main water supply system (via the water tower) from leaking above-ground tanks and below-ground tanks in the Petroleum, Oil and Lubricant (POL) Bulk Storage Area from the 1970s through April 1985. The plume was discovered in 1979 and was named the Benzene Plume. The main wells were relocated in 1985. The leaks were discovered from 1990-1992 and the offending storage tanks were removed. This contamination plume requires more study to determine how much of these harmful chemicals likely reached the faucets on base. |

| WARNING! According to the record, stand-alone wells like AF22 at Burkhart Lodge, drew in harmful quantities of jet fuel (JP-4) and used engine degreaser (TCE) from the Weapons Storage Area from the 1970s-1997. This is officially called the Pierces Point Plume, which leads to Van Etten Lake. This same plume, contains a major firefighter foam contamination from an above ground tank rupture in January 1989. Arman and their families using the Burkhart Lodge alert crew recreational facility likely drank harmful quantities of both volatile and non-volatile chemicals. |

By April 1985, Wurtsmith IRP officials published their first administrative report after conducting a base-wide records search. The records search focused on collecting past waste handling records to determine disposal practices and included interviews with past and present base employees. Problem Identification and Records Search was the first phase of the four-phase program. The other phases were Problem Confirmation and Quantification, Technology Development, and Corrective Action. That same year, USGS published its final water contamination report. Building on the 1985 results of the USGS water reports and the IRP records search report, the IRP officials identified 53 potential contamination sites: 7 leaking underground storage tanks, 9 landfills, 2 fire-training areas, 29 spill sites, 4 surface impoundment areas, and 2 sludge drying areas. This is roughly all base officials knew about the contamination problem in 1986.

After reading the official contamination and health reports from 1983 to present, it is clear base officials were only beginning to understand the depth and scope of the base-wide volatile chemical contamination problem in the spring of 1986. The ultimate goal of remediation or correctives was a long way off. The story of  the Benzene Plume is a good example of how little base officials knew at the time. The Benzene Plume eventually become the most egregious groundwater volatile chemical contamination; a volatile chemical contamination larger than the 1977 Arrow Street Plume filled with TCE. The Benzene Plume never gains the notoriety it deserves because it took over 13 years to determine the source was a leaking above ground tank filled with jet fuel. It is likely the unknown jet fuel leak prompted the movement of the main base wells to another location in the Spring of 1985. The decision to move the wells was catastrophic because the new wells were placed adjacent to a firefighter foam disposal site. Following is the jet fuel groundwater contamination story, which was incrementally drawn into the main drinking wells at Wurtsmith.

the Benzene Plume is a good example of how little base officials knew at the time. The Benzene Plume eventually become the most egregious groundwater volatile chemical contamination; a volatile chemical contamination larger than the 1977 Arrow Street Plume filled with TCE. The Benzene Plume never gains the notoriety it deserves because it took over 13 years to determine the source was a leaking above ground tank filled with jet fuel. It is likely the unknown jet fuel leak prompted the movement of the main base wells to another location in the Spring of 1985. The decision to move the wells was catastrophic because the new wells were placed adjacent to a firefighter foam disposal site. Following is the jet fuel groundwater contamination story, which was incrementally drawn into the main drinking wells at Wurtsmith.

The USGS discovered the Benzene Plume in 1979, which led investigators to suspect the base Petroleum, Oil and Lubricant (POL) Bulk Storage Area. The POL storage area stored jet fuel, heating oil, gasoline, diesel, and deicer. The storage area had aboveground storage tanks (AST) and underground storage tanks (UST). Over time, other nearby tanks were considered part of the POL storage area because of their proximity to each other, the shared portion of the aquifer, and the leading contamination from the overall area was jet fuel. As defined, the storage area was comprised of the following:

- 1.26-million-gallon jet fuel AST

- 568,000-gallon jet fuel AST,

- 210,000-gallon heating fuel AST

- 315,000-gallon heating fuel AST

- 2,000-gallon military operational gasoline (MOGAS)

- 2,000-gallon waste heating oil recovery UST

- 10,000-gallon diesel fuel tank UST

- 12,000-gallon gasoline tank UST

- 550-gallon diesel tank UST

After laboratory testing in 1979, it was determined that the benzene in the Benzene Plume was from jet fuel. The military jet fuel at Wurtsmith AFB was JP-4, which is half kerosene and half gasoline. JP-4 was the primary military jet fuel for the Air Force from 1951 to 1995. According to early USGS, Wurtsmith AFB water contamination reports, Benzene is only 1-2 percent of the chemical composition of JP-4. This estimate is likely high as material data sheets list Benzene as only 0.50 percent of JP-4. To put this in perspective, finding a gallon of Benzene underground means that roughly 200 gallons of jet fuel is the actual amount of the underground contaminate. Investigators decided in 1983 that the cause of the JP-4 in the groundwater was from a spill and not from a leaking tank. At the time, Wurtsmith AFB did not implement the purging schema suggested by the USGS.

By 1985, the Benzene Plume was somewhat larger and had shifted northward. This time, JP-4 was floating on the surface of the water table near the bulk-fuel storage area. This was a new development that investigators had not seen up until this time. The presence of jet fuel was not in question because it looked and smelled like JP-4. Tests confirmed the obvious. Again, investigators decided the fuel was not from a leak of a storage tank or the underground Harrisville pipeline leading to the tanks. Investigators eliminated the pipeline as the source of the leak after digging up and inspecting the section of pipe near where the JP-4 floated on the aquifer. Again, USGS investigators decided the jet fuel was from a surface spill and not a leaking tank in the bulk-fuel storage area. In 1986, USGS investigators again recommended a modified purge plan, and Wurtsmith AFB did NOT implement the plan.

It was not until six years later, in 1992, that base officials would discover a leak in the 1.26-million-gallon JP-4 AST. This led to the removal of the tank by the summer of the same year and the addition of a Benzene pump and treatment system shortly thereafter. It would take thirteen years for investigators to discover this leaking tank after finding Benzene in the aquifer in 1979. How long the JP-4 tank was leaking before this time is unknown. How much went into the groundwater is also unknown. Two years earlier in May 1990, base officials had already discovered and removed two other leaking tanks in the POL area: The 2,000-gallon waste oil recovery UST and diesel fuel UST. When and how long these tanks leaked is also unknown.

Shortly before my wife and I arrived at Wurtsmith AFB base, officials did not know of any active leaking storage tanks. By 1990 when the Air Force moved our family from Wurtsmith AFB to access better medical facilities for our newborn handicapped son, base officials identified seven leaking USTs and would discover a short two years later the source of Benzene Plume, a leaking 1.2 million-gallon JP-4 above ground tank. The removal of the leaking tanks took place shortly before and after the base closure activities, which officially started in July 1991. Wurtsmith AFB closed its doors two years later in June 1993. Shortly after the base closed, a Final Environmental Impact Statement depicted an IRP site map of Wurtsmith AFB. The map shows the Arrow Street Plume and POL Storage Area Plumes discussed above. In addition, the map depicts the Mission Street Plume, Operational Apron Plume, Inactive Weapon Storage Area Plume, Pierce’s Point Plume, Northern Landfill Plume, and Fire Area Training Plume. Contamination plumes cover roughly one-third of the base public working and living area.

Air Force Plan to Stop Toxic Lake Foam ‘a Step in the Right Direction’, MLive.com, August, 27, 2020. https://www.https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2020/08/air-force-plan-to-stop-toxic-lake-foam-a-step-in-the-right-direction.html?fbclid=IwAR1l780hkaxDKPT0eB7yB-M0YBe46uT-bQzZx6DeZljZA8qXwlfYw4QZghkmlive.com/public-interest/2020/08/air-force-plan-to-stop-toxic-lake

“History will likely record that the groundwater chemical contamination on military installations harmed our Veterans like Agent Orange in Vietnam and the burn pits in Iraq. Unlike the chemical contamination of veterans on foreign soil, the groundwater contamination at home unfortunately impacted the warfighter’s families and the surrounding communities” (OVERWHELMED: A Civilian Casualty of Cold War Poison, 2019, p. 277)

AUTHOR: This bulletin was written by Craig Minor

- USAF, retired. Wurtsmith Air Force Base B-52G Aircraft Commander; Wright-Patterson Air Force Base NT-39A Instructor Research Pilot and Senior Acquisition Manager, 2016

- BS Chemistry, Averett University, Danville, Virginia, 1984

- MBA in Finance, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio 2004

- JD in Law, Capital University Law School, Columbus, Ohio, 2013

Co-author of “OVERWHELMED: A Civilian Casualty of Cold War Poison; Mitchell’s Memoir, As told by His Dad, Mom, Sister, & Brother, 2019.”

Sources and End Notes

United States Geological Survey (USGS), 1983. Ground-Water Contamination at Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Report 83-4002.

United States Geological Survey (USGS), 1986. Assessment of Groundwater Contamination at Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Report 86-4188.

Montgomery Watson, 1993. Final Environmental Impact Statement, Disposal and Reuse of Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Michigan. September.

US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001. Public Health Assessment Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Michigan. April.

Air Force Real Property Agency (AFRPA), 2004. First Five-Year Review Report for Installation Restoration Program Sites at Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Michigan. September.

US Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. Evaluation of Drinking Water near Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Michigan. September.

US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018. Re-evaluation of Past Exposures to VOC Contaminants in Drinking Water Former Wurtsmith Air force Base, Michigan. July.